The earliest records of the poor in Ireland.

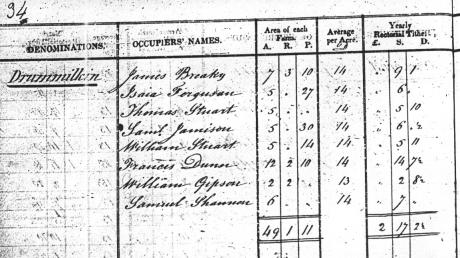

The Tithe Applotment Books were compiled between 1823 and 1838 as a survey of titheable land in each parish. They do not cover urban areas. In general, the information contained in the records is as follows:

- name of occupier

- name of townland

- acreage

- classification of the land

- amount of tithe due

The tithe applotment books are available for consultation on microfiche in Dún Laoghaire. The originals are held in the National Archives. The Northern Ireland books are held by the Public Record Office of Northern Ireland (PRONI).

The Mayo County Library has a MicroFiche copy of the Tithe Applotment books for Shrule.

search records here

Tithe Applotment Books

Tithe Applotment Books date from the decades prior to the famine and the mass emigration that followed it. They record the amount of Irish tithe, ie tax, due from each occupier of land, regardless of his religion, to support the clergy of the (Protestant) Church of Ireland.

Originally the tax – of one tenth of production – was paid by the farmer in produce. But in 1823, the Tithe Composition Act was introduced and allowed tithes to be paid in cash (actually, this had already become a fairly widespread practice).

The Act also launched the Tithe Applotment Survey, a valuation of the entire island. Carried out civil parish by civil parish, the objective of the survey was to determine how much tithe each occupier of land ought to pay. The records contained in the Tithe Applotment books are arranged by townland and list the names of the each land occupier, the size and quality of their land, and the tithe deemed payable.

The tithe was calculated on the average price of oats and wheat between 1816 and 1823, while the quality ie productivity of the land was graded between 1 and 4, very good and very poor respectively

Converting the values into modern currencies is pretty much meaningless but you can get an idea of how well off or badly off your ancestors were by simply comparing them to others in their townland.

Converting the values into modern currencies is pretty much meaningless but you can get an idea of how well off or badly off your ancestors were by simply comparing them to others in their townland.

You may come across the addition of ‘and partners’ or ‘and Co’ beside some entries in the Tithe Applotment books; this annotation does not suggest the formation of a business, but rather that land was held by a number of tenants in common.

The value of Tithe Applotment Books to Irish genealogists

The Tithe Applotment Books record the occupiers of tithe-eligible land, not householders. It was not a population census.

Tithe Applotment Books are arranged by parish and contain the following information:

- Land occupier’s name

- Townland

- Area of landholding in acres

- Land assessment grade 1-4

- Calculation of tithe amount

Because the tithe was payable only by those who worked on agricultural land, you may not find your ancestors included.Those labourers who worked on agricultural land owned by the Church were exempt. So, too, were those labourers who did not rent land, as were those who lived and worked in urban areas.

Even so, the books represent the earliest records for the poor of Ireland, a group for whom very few other genealogical records survive from this period.

In fact, if your ancestors lived in one of the rural church parishes for which no pre-1850 records exist, Tithe Applotment books may also be the only records available.

The books are on microfilm at the National Archives and National Library in Dublin, and through LDS Family History Centers.

The Tithe War 1830-1838

Quite apart from the obvious dislke for paying hard earned money to a minority church, the tithe was hated among Catholics because the poor (as ever) bore the brunt. Indeed, some wealthy landowners didn’t pay anything while some tenants had to pay even though they farmed little more than a tiny potato patch. By the end of the 1820s, anger about these inequalities had reached a new level.

Although history records the subsequent protests as the Tithe War, it was really only a rural campaign against the hated system.

Protests had been made before. Groups known as the Whiteboys, the Oak Boys (1763) and the Hearts of Steel (1770s) had come and gone, but after the success of the campaign for Catholic emancipation, which was granted in 1829, there was a more widespread belief that protests could achieve desired results. A major distinction of the Tithe War was that this campaign had the support of larger farmers and the Catholic clergy.